The limitations of the UN ceasefire for Yemen

| Getting your Trinity Audio player ready... |

By Jonathan Fenton-Harvey*

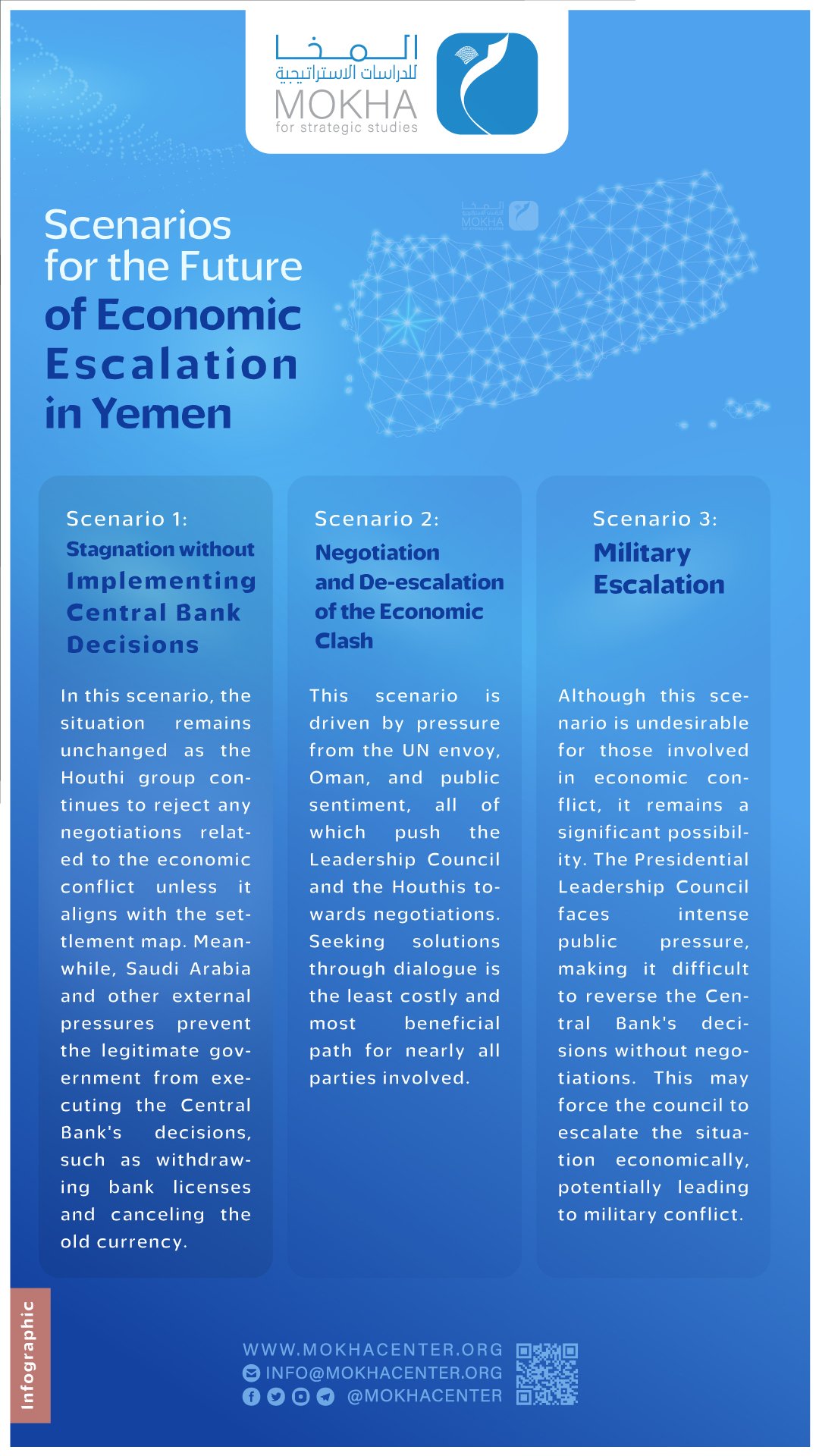

Yemen’s two-month ceasefire on April 2 has passed its two-month deadline, as it was scheduled to end on June 1. It initially raised hopes that peace in Yemen’s brutal war, now in its eighth year, could finally come to an end. Although the ceasefire has now been extended, there have been various fractures within the ceasefire, indicating that more needs to be done to achieve lasting peace.

The ceasefire also entailed the reopening of the roads around the city of Taiz, running two commercial flights a week between Sanaa and Jordan and Egypt, and enabling 18 fuel vessels into the port of Hodeidah, which has been blockaded by the Saudi-led coalition and is controlled by the Houthis.

A Glimmer of Hope

Although the truce was set to expire, raising fears of further violence and prompting calls from humanitarian agencies to extend it to save Yemeni lives, as tensions and even hostilities remained, the ceasefire has once again been extended. On the morning of June 2, the UN announced that it had managed to broker an extension of the two-month ceasefire, and said that it had received “preliminary, positive indications” from Yemen’s warring parties.

Delegations from the Saudi-backed and internationally recognized Yemeni government and the Houthi movement are expected to return to the Jordanian capital Amman to continue talks.

Yemen’s war took a turn for the worst in February 2021, after the Houthis renewed their long-standing offensive to capture the Government-controlled governorate of Marib, and subsequently making further pushes to conquer parts of the country. This came after US President Joe Biden announced an end to ‘relevant’ arms sales to Saudi Arabia, which the Houthis evidently sought to exploit.

The Houthis then looked to expand eastwards and southwards in Yemen, renewing their quest to conquer the entire country. While it prompted an increased Saudi intervention in the country, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) also renewed its operations against the Houthis, to protect its geopolitical aspirations in the south of Yemen.

The ceasefire had therefore created a glimmer of hope that Yemen’s war, which has lasted for more than seven years, could finally end. It followed other optimistic signs, such as the resignation of President Abed Rabbuh Mansour Hadi’s resignation and the formation of an eight-member Presidential Council. Although Hadi was the internationally recognized President, he had little authority on the ground, and his removal was one of the Houthis’ preconditions for peace talks.

Other extra positive signs had occurred following the ceasefire, including the exchange of prisoners. The Saudi-led coalition announced on May 6 that would release a small number of Houthi prisoners to Yemen, though the Houthis claimed these were not aligned with the movement.

During the first month of the ceasefire, civilian casualties had reduced by over 50 percent. This figure indicates that while the violence had continued, the ceasefire was able to reduce the fighting. Yet it also shows that violence could continue even during peace times, thus highlighting the drawbacks of UN peace efforts.

Continued tensions

On the one hand, the warring parties had substantially reduced their violent operations. Saudi Arabia had stopped operating its airstrikes, and it had even reportedly allowed 12 ships to unload fuel at Hodeidah port – despite the truce requiring 18 fuel ships. Meanwhile, a small number of flights were allowed to resume from Sanaa airport, including the commercial flights, after it was blockaded throughout the war, few flights were also allowed to leave Sanaa airport.

However, the Saudi-led blockade – which Riyadh claims is to limit the flow of Iranian weapons and support to the Houthis, has largely remained in place and this could be a continued obstacle for a peaceful solution – asides from it exacerbating the humanitarian crisis.

And while the Houthi rebels have stopped firing rockets into Saudi territory and scaled back their own operations, the group has still tried to consolidate its position key territories like the Marib governorate and the city of Taiz.

Crucially, the conflict over Taiz has been a central focal point for the UN-sponsored initiatives. Taiz, which is Yemen’s third largest city, has been heavily contested throughout the war and remains a crucial area where a power struggle has occurred.

On May 28, the UN announced it had failed to achieve a resolution over Taiz which could end the Houthis blockade over the city. Subsequently, Houthi firing had renewed on the city, showing that the fragile efforts to end violence over the city had faltered, revealing the international community’s limited leverage over the war and how its current stance is not enough to broker peace.

Further showcasing the friction between the warring sides, both the Coalition-backed Yemeni government and the Houthis had accused one another of violating the ceasefire. The internationally-recognized government said that the Houthis had carried out assaults in Taiz and Marib, while the Houthis’ proclaimed Defence Minister Mohammad al-Atifi claimed that the Saudi-led coalition had carried out ceasefire violations including operating drones across various governorates.

Going forward

The Houthis have indicated that they are willing to make concessions should Hadi stand down from power. Yet given that the faction launched the latest stage of Yemen’s war, it would be up for the faction to ensure that the peace efforts could last. And while the ceasefire is indeed crucial in order to contain further violence, it is important to provide lasting pressure on warring actors and make robust efforts to ensure that peace talks can prevail.

On Wednesday, nearly 50 members of the US Congress introduced legislation to invoke constitutional war powers to fully end illegal US support for the Saudi-led coalition.

Even if the Saudi-led coalition continues to scale back its intervention, Saudi Arabia and the UAE could make further efforts to ensure their desired actors gain a stake in Yemen, for the sake of their geopolitical aspirations. This would hinder Yemen’s long-term stability and undermine any external peace initiatives, whether from the UN or the US.

While the US’ full removal of support for Saudi Arabia is crucial for ending the war, it is important to remember that the Houthis’ compliance would also be crucial. Given Riyadh’s relative drawdown, the future of Yemen’s conflict may also largely be in the hands of the group.